Black Bodies, White Babies: Evolution of an image

“I must have known that the portraits had historical precedent. I must have felt compelled, on some level, to recreate them– except with myself, a black woman and a nanny, behind the camera.”

I. Proof of Life

I began photographing Ellery because she was so exquisite– rolls on rolls on beautiful rolls of soft, luscious body– bulging out of her clothes like warm marshmallow pressed between graham crackers. When she entered a room, it was chin up and belly first. When she lounged, it was like a Reuben painting. Also, the girl could pose. Even now, when I study the photographs— the way she would gaze, unsmiling, at the camera, with a confidence beyond her years— I wonder, was I imagining it, or was she finding her light, aware of her angles? Ellery was 4 months old when I began photographing her, and I was her nanny.

Ten years before I met Ellery, I was a young nanny with a Blackberry and not much interest in photography. Taking pictures of the children in my care began as a practicality, if not a requirement of the job. It was a way to ease the minds of anxious parents who could not be with their children during the day— essentially, proof of life. I would receive daily texts from an employer asking “how is everything?” and I would respond with a quick snapshot of a radiant smile, to prove beyond a doubt, in a way that words would not, that all was well. The photos meant a lot to parents, and I was happy to take them. Send a really good photo, and I wouldn’t hear from them for the rest of the day.

My early photographs tended to capture the children smiling or eating or engaged in play, all their exuberant blondeness playing directly to the camera as if to say “See, mom– I’m okay!!!” Over time, as I gained the trust of my employers and experience as an amateur photographer, I started thinking more about lighting and composition. Also, my phone’s camera got more and more sophisticated. I developed a style of shooting that felt more organic and less disruptive to our play. I began to hold the phone horizontally and at odd angles, low to the ground or off to the side, while keeping my full attention on interacting with the child. The images were candid and often depicted humorous angles. I eventually expanded my repertoire to include pictures of the children crying or angry. I would delight in capturing those very subtle expressions that only the very few who really knew the child would recognize as so– them. Even as the only audience for my photographs remained the children’s parents (and sometimes my grandma), the act of taking the photos had taken on a larger personal purpose, both of documenting the work, and keeping my artistic brain engaged.

When I met Ellery, it was in my tenth year of working as a full-time nanny, and as I mentioned, she was the most deliciously plump baby I had ever had the privilege of squeezing. She seemed to delight in her body; and because I happened to be going through a period of delight in my own body, I got the idea of posing with her for portraits. I wanted to capture our shared confidence and energy, but also the beautiful contrast of our bodies together.

To capture the photos, I set my computer’s camera on a timer, usually just before or after a nap, when we were most physically connected, and we both just hammed for the camera. Ellery required almost no coaching. She was a preverbal infant, so it was really more of an energy exchange, between us and the camera. The resulting pictures are powerful and humorous. The story they tell is one of love, trust, and empowerment. Our bodies look amazing. We posed for portraits many times over the 18 months that I was her nanny. Eventually, as she became more mobile and less interested in sitting, the ritual dropped off. Not long after, she and her family moved across the country, and I began photographing a new baby.

II. Parallel Images

In 2019, I was accepted into OHMA and began work on an oral history project about career nannies working in new york. As part of my research, I began collecting historical portraits of women of color posing with the children in their care. The women in these photographs were nannies, maids, and enslaved women. They posed sitting or standing, with a white child, gazing, unsmiling, into the camera. The exposure of some of the earliest images often caused the black caretaker’s features to be obscured by shadow or the white child's features to be obscured by light. Each photograph is a complicated mix of tenderness, defiance, love, and exploitation. As I gathered the photos in a digital album, I began to notice the similarities to the composition of my own portraits. I started a document placing the historical images side by side with my own portraits, and the similarities could not be ignored. The subject matter on the most obvious level was: black bodies, white babies.

Seeing these images juxtaposed, I immediately felt deep discomfort. It was not that I had not considered my connection as a nanny to a long history of black women caring for white children, it was just that I hadn’t intended to draw the connection so starkly. It was not just the sensitivity of the historical images but the heavy-handedness of the connection. How would viewers, and particularly the parents of the children depicted with me, feel to see these playful images recontextualized this way? Was it a fair recontextualization?

The discomfort was made worse by the fact that these parallel images felt unplanned, if not accidental. I had not set out to recreate historical photos of oppressed and enslaved women with white children. I felt the need to add some kind of disclaimer before showing anyone the images, that the similarities were purely coincidental. Of course this was only half true. It was true that my photoshoots with Ellery were spontaneous and served a personal purpose. However, somewhere in my subconscious, I must have known that the portraits had historical precedent. And more importantly, I must have felt compelled, on some level, to recreate them– except with myself, a black woman and a nanny, behind the camera.

III. Reclamation

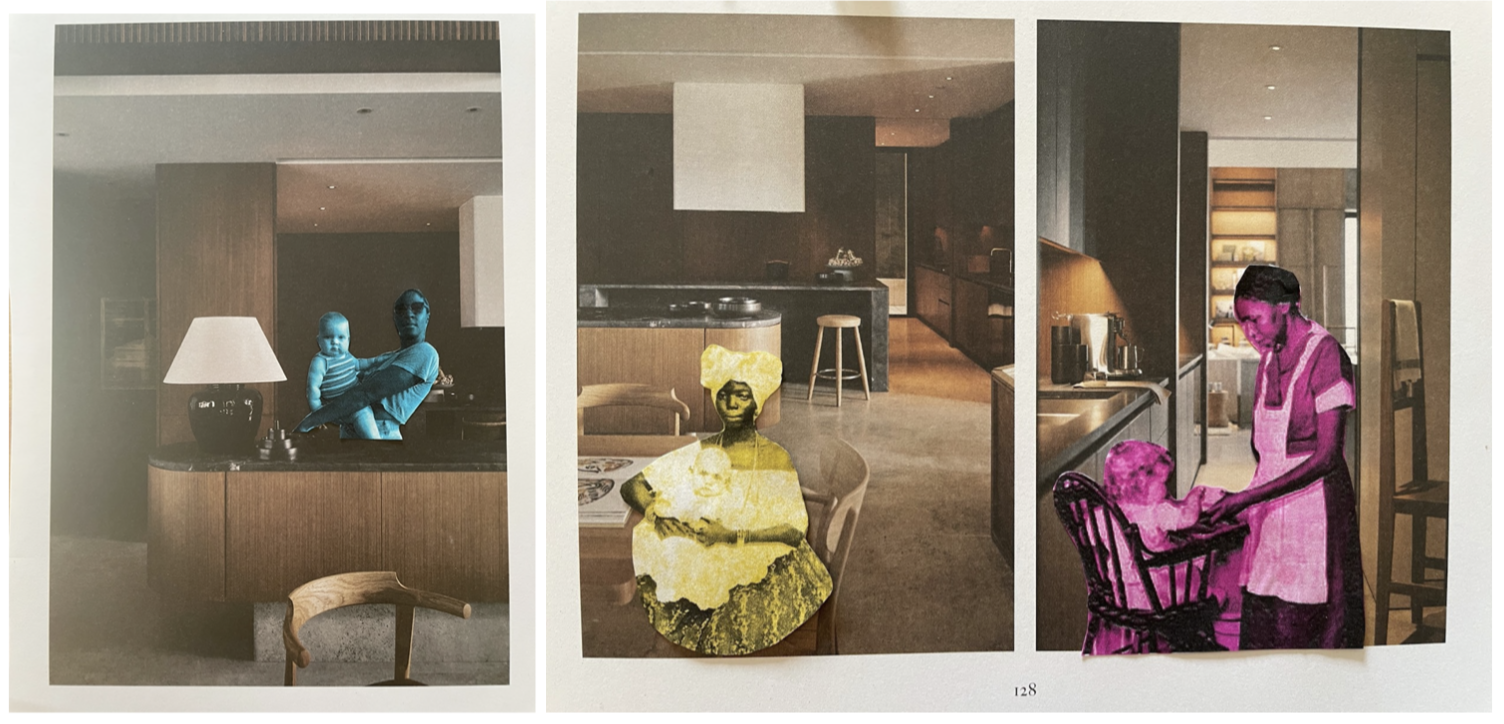

Working with collage began in the late stages of curating my thesis project, as a restorative practice. It was a way to interact with the “materials” without engaging with technology. I had decided not to include the parallel image experiment, but found myself returning to the photos often for inspiration. I decided to print them, and then went to Michael’s and purchased a dozen small 8x10 canvases. My next stop was Barnes and Noble, where I purchased several architecture and Home Living magazines. My goal was to work small and quickly, creating collages in 5-10 minutes to reset my brain for audio editing and writing. Collaging, I found, was the most physical and profound translation of the motherwork of the whole project. The process of physically touching the historical images, my own photography, canvas, and glue, mirrored the process of making and processing in sound and words. It was an opportunity to address some of the embodied experiences that could not surface in the audio interviews. The images are created from architectural magazines, historical photographs, and my own archive of personal photography. Unlike the parallel images, I was also able to make use of the historical images of black mother-workers in a way that was both playful and provocative. I got to play with color and space to reiterate some of the themes I explored in words and sound.

By bringing generations of mother-workers together and in color, against a modern, sterile backdrop, the images felt more connected and more empowering. I found that printing in pop art colors– bright pinks, blues, and greens– suggested a hint of satire. I played with the cut-out figures like paper dolls, placing them in various backgrounds and then photographing the collage, often without gluing. I experimented with bringing the figures to the foreground and pushing them to the background, hiding them behind pillars, and placing them in doorways. Each composition changed the energy of the scene in complex ways.

IV. Accountability

As I write this, I am preparing to show the collages to Ellery’s parents. I want to seek their consent to use their daughter's image in my project design. I also want to make space for whatever complicated feelings they may have about the juxtaposition of our bodies with the historical images. I feel hopeful that the conversation will lead to new avenues of thought for us both. I feel confident for the same reason that the photos exist in the first place. This was a job where my artistic expression had room to breathe. It had room to breathe, because I had my employers' trust and respect. They not only acknowledged me as an artist, but they did so while I was working as their nanny. They gave me space. They paid me on time. When I told them I wanted to apply for graduate school, they helped me to create a resume that would legitimize and honor all the work I had done behind closed doors for ten years. They shared their daughter with me, gave us space to connect and play, and then, when it was time, they let me go. If you are reading this now, it is with their consent and support.